About the Queensland Shark Culling Program (QSCP)

The outcome of Humane Society International (Australia) Inc v Department of Agriculture & Fisheries (Qld) AATA Case proved "overwhelmingly" that mesh nets and catch-and-kill drumlines used by these programs do not make any impact on safety, negatively impact on the marine ecosystem, and provide beachgoers with a false sense of security.

They ruled that these methods must cease to be used within the bounds of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

"The lethal component of the SCP does not reduce the risk of unprovoked shark interactions. The scientific evidence before us is overwhelming in this regard."

- Humane Society International (Australia) Inc v Department of Agriculture & Fisheries (Qld)

What it is

The Queensland Shark Culling Program, also known as the Shark Control Program, has operated since 1962 at selected beaches. Shark nets and drumlines are set offshore from over 80 beaches, and checked 'regularly' throughout the year. The program aims to reduce the risk of shark interactions by catching and killing large sharks in an attempt to reduce their populations. Whilst the language surrounding the program has evolved over the years, including removal of explicit references to culling, the program has fundamentally remained the same.

What this means in practice

-

The Shark Control Program is at its core, a shark fishing/culling program, based on the 1960's premise that lower shark populations means safer beaches.

-

Shark nets are not barriers; they are short 150m sections of mesh fishing nets, set parallel to the beach. They do not keep sharks away or create an enclosure of any kind.

-

Shark Nets are by nature not species specific, and catch both target species (white, tiger and bull sharks etc.) and non‑target animals. Over 50% of catch historically is non‑target species.

-

Catches include protected wildlife such as dolphins, turtles, rays and humpback whales - which would be illegal and prosecutable offences, but DPI is provided an exemption under the Fisheries Act 1994 (Queensland).

-

Catches often die slow, painful and cruel deaths, which is in breach of the Animal Care & Protection Act 2001 (Queensland), however the Government has inserted an exemption for the SCP into the legislation as a way to allow it to operate despite it's inherent cruelty. The exemption does not apply in all cases.

Credit: Erin Kirkwood

How Shark Nets Operate

Operation

-

Nets are installed year-round at selected beaches.

-

Mesh size and placement are designed to entangle and kill animals.

-

Caught animals may be found alive or deceased at routine inspections. These occur 'regularly' or as weather permits.

Important Considerations

-

When animals are caught, odours and distress cues can attract sharks to the area.

-

DPI has not assessed any additional risk created by this side effect of the program for swimmers and surfers.

-

General DPI "Shark Smart"safety advice is to avoid swimming near fishing activities.

Credit: Humane World for Animals

Effectiveness and Limitations

Fatal shark bites per capita had an all time peak in the 1930s in QLD, and steadily decreased since.

The introduction of shark nets and catch-and-kill drumlines in the 1960s is often cited as the reason for the reduction in fatal shark bites after the 1960s, however this ignores the same trend from 1930s-1950's with no shark nets or drumlines present.

Whilst this simplistic correlation of trends post 1960s may seem like evidence that shark nets work, correlation does not equal causation. Shark nets are fully removed during bad weather, and lethal catch-and-kill drumlines were removed from the GBRMP due to a court order. During neither of these periods, are there increases in shark bites.

Various peer-reviewed scientific analyses, including one co-authored by DPI scientists, indicates there is no clear scientific evidence that reducing local shark numbers through meshing reduces risk at beaches.

The reduction in fatalities since 1960s is instead attributed to other factors such as faster intervention from lifeguards and first responders, faster transport times to hospitals, and improved medical care for severe trauma, since the 1960's. In some regions shark nets may go many years without catching any target sharks resulting in 100% bycatch, meaning that even if the belief is held that catching and killing target sharks is effective, the program is unsuccessful at this.

"We could not detect differences in the interaction rate at netted versus non-netted beaches since the 2000s, partly because of low incidence and high variance. Although shark-human interactions continued to occur at beaches with tagged-shark listening stations, there were no interactions while SMART drumlines and/or drones were deployed."

Credit: Envoy Foundation

Image credit: Envoy Foundation

Shark Drones more effective than shark nets and drumlines

A drone trial revealed 676 sharks were sighted across SEQ beaches, compared to just 284 caught in Shark Control Program nets and drumlines. Notably, at North Stradbroke Island and Burleigh Beach, sightings were significantly higher (NSI: 314 vs 32; Burleigh: 168 vs 24), even though drones operated for only ~2% of the time compared to shark control gear.

This shows that drones provide:

-

Sharper Detection: Drones recorded significantly more shark sightings with far less time in operation—highlighting their potential as a real-time monitoring tool that spots more than lethal methods.

-

Enhanced Safety: Larger sharks can pose greater threats to beachgoers, so spotting more of them via drone surveillance offers crucial early warning.

-

Conservation-Friendly: This method avoids the indiscriminate harm of nets and drumlines, strengthening the case for non-lethal, tech-based alternatives.

Mitchell et al (2025)

Queensland SharkSmart Drone Trial (2020 - 2024) Final Report

Environmental Impacts

Nets capture many non‑target and protected species. This killing of protected species is permitted under The Fisheries Act 1994 (Queensland), which provides a legal defence for otherwise protected wildlife deaths.

Dolphins & Whales

Entanglement events occur during the meshing season. Animals may be released or recovered deceased.

Turtles & Rays

Several turtle species and large rays are susceptible to entanglement. These species are otherwise protected under NSW and Commonwealth law.

Non‑target Sharks

A high proportion of catch comprises harmless or threatened sharks (e.g. Grey Nurse and Scalloped Hammerheads).

Survival Rates

Released animals are often not tagged or tracked and actual survival rates or post mortality rates are unknown.

Image credit: Erin Kirkwood/Envoy Foundation

A History of Whale Entanglements

Each year, a staggering number of whales, often mothers and calves, become entangled in the QLD shark nets.

Despite mounting public concern and expert recommendations, the Queensland Government has opted to maintain shark nets during whale migration season. This decision contradicts advice from its own Scientific Working Group and an independent review conducted by KPMG, both of which recommended removing the nets during peak whale movements, as NSW has done since 1989.

This year’s entanglement numbers already place 2025 among the worst seasons on record for humpback whale entanglements in Queensland shark nets:

2019 – 5

2020 – 6

2021 – 4

2022 – 15

2023 – 11

2024 – 8

2025 – 11 (and counting…)

DPI add whale pingers to the nets, claiming that they deter migrating humpback whales from becoming entangled in shark nets. The shear number of whales that do get entangled in the nets is evidence in itself that these pingers do not work.

DPI continuously and disingenuously promotes whale pingers as a solution for whale entanglements, and makes these claims on the basis of studies with methodologies that bear no relevance to the QSCP. It does this, while ignoring stronger evidence that shows pingers are ineffective with methodologies that bear more relevance to the QSCP.

When questioned about the effectiveness of whale pingers on shark nets to stop migrating humpback whales from becoming entangled, DPI pointed to a study conducted in Iceland, namely Behavioural Responses of Humpback Whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) to Two Acoustic Deterrent Devices in a Northern Feeding Ground off Iceland (Basran et al 2020). This study investigated the use of whale pingers as a potential tool to reduce whale entanglement of feeding humpbacks in purse seine nets. Both the behaviour (Humpbacks do not feed around shark nets) and the equipment (purse seine nets are not at all similar to shark nets) are very different to the context of QSCP. This study found that pingers may reduce entanglements, but only in specific circumstances, such as when humpback whales are feeding in certain areas. The study therefore recommended that pingers should be used only as a shortterm solution, in combination with other mitigation methods, to avoid negative impacts on whale behaviour.

In contrast, another relevant study has been explicitly ignored by the department when they have been requested to remove language suggesting pingers are effective. The study A whale alarm fails to deter migrating humpback whales, (Harcourt et al 2014), found that pingers were ineffective at deterring migrating humpback whales. This study’s methodology is much more directly applicable to the QSCP context, as it examined the use of pingers in areas where whales are migrating on the East Coast of Australia — conditions similar to those in which the QSCP operates. The department has dismissed this research, claiming that the methodology and configuration of the pingers used in the study do not reflect how pingers are used in the program.

Attractant Effect of Shark Nets

Caught or decomposing animals can release odours and produce sounds of struggling prey. These cues are known to attract sharks. DPI holds extensive photographic records of sharks feeding on animals caught in shark nets. There has been no assessment or research on any additional risk this may present to swimmers or surfers near shark net locations.

Animal Cruelty

Under Queensland law, cruelty to animals is a serious offence. The Animal Care and Protection Act 2001 (AC&P Act) prohibits acts that cause unnecessary harm or suffering to animals, with penalties including fines and imprisonment.

Yet the Queensland Shark Control Program (QSCP) routinely carries out actions that would otherwise be considered criminal animal cruelty, such as the slow and painful deaths of sharks, turtles, dolphins and other marine life caught in nets and drumlines.

So how does it continue?

The QSCP is granted a special legal exemption under Section 46 of the AC&P Act. This exemption allows animal cruelty to occur if it meets specific criteria:

-

The cruelty must be carried out using fishing apparatus,

-

It must be for the purpose of protecting people from shark attacks,

-

And it must be done under a valid government contract.

The problem...

These conditions are not being met.

-

The exemption refers to fishing, not indiscriminate wildlife killing.

-

Legal findings have shown there is no proven threat from the sharks being targeted.

-

Contractors are not always complying with the method or legal framework required by the exemption.

Without this loophole, many QSCP activities would likely be prosecutable under Queensland’s animal cruelty laws. This is not only a legal failure, it’s an ethical one.

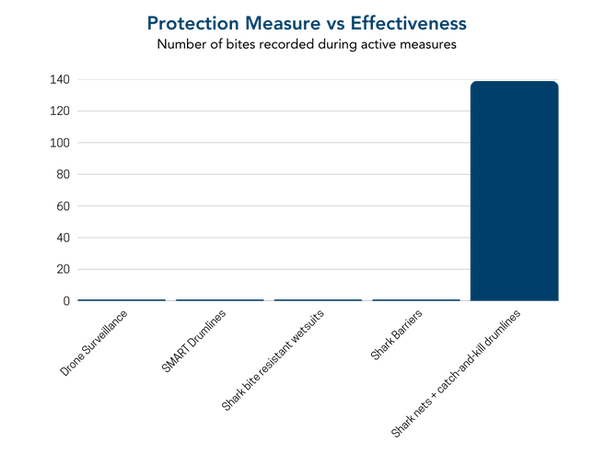

Modern, Non-lethal Measures

NSW and other jurisdictions use additional measures that maintain beach safety without the environmental costs of meshing.

Drone surveillance

Trained pilots monitor nearshore waters and alert lifesavers. No shark bites recorded during active drone surveillance.

SMART drumlines (non‑lethal)

Tagged sharks are relocated offshore. No shark bites recorded during active, non‑lethal use.

Shark barriers / stinger nets

Fixed enclosures for swimming areas. Physical separation with no bycatch; zero recorded bites within barriers.

Personal deterrents

Independently tested electrical deterrents reduce risk for individuals.

The Myth of Territory

One of the central justifications for the Government’s shark net program is that nets supposedly prevent sharks from establishing “territories” near beaches. This claim is seems to have originated in NSW as opposed to QLD, however it is often repeated in QLD and warrants investigation.

A Claim Without Science

The NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) has repeated this claim across various official materials — from their website to public statements. But if you dig into the science (as we did), the evidence doesn’t stack up:

-

2009: The NSW Fisheries Minister at the time described the nets as a “psychological barrier” in Parliament — with no supporting data.

-

2015: The DPI clarified there was no scientific evidence that sharks aggressively defend small, localised territories. Their attempt to redefine “territory” to mean loose aggregations doesn’t hold up scientifically.

-

Senate Inquiry Submission (2017): Multiple experts challenged the claim, citing long-distance tagging data that shows species like great whites and bull sharks are highly mobile — not territorial.

-

Internal DPI documents: Describe territorial prevention as a goal, not a proven outcome.

-

2025: NSW DPI finally admitted that sharks do no establish territories, confirming, without admitting, that their previous statements have been false.

Put simply: shark nets don’t stop sharks from establishing territories, and the concept of shark “territories” around beaches isn’t scientifically grounded to begin with. The 2009 claim in Parliament may have been the origin of these claims, which seem to have been retrospectively created long after the meshing program started, as a way to justify the shark net program.

No Defined Protection Area

Despite operating the program since 1937, DPI does not provide any guidance around key questions related to the effectiveness of nets:

-

What size or shape area around a net is considered “protected”?

-

Is the “protected” zone defined by a radius or straight lines? What are the dimensions?

-

How is a netted beach defined in incident reports, especially when shark bites occur nearby?

Why This Matters

There is no evidence of shark nets stopping sharks from forming territories, and the area of protection (if any) is not defined by DPI. Any claims regarding deterring the establishment of territories, or protection provided by shark nets, is not supported by evidence or research, and should not be made by Government or media.

Swim Safely

The Queensland Government's SharkSmart website provides the below tips to being 'shark smart' when in the water.

-

Swim between the flags at patrolled beaches and check signage

-

Have a buddy and look out for each other

-

Avoid swimming at dawn or dusk

-

Reduce risk, avoid schools of bait fish or diving birds

-

Keep fish waste and food scraps out of the water where people swim

-

Swim in clear water away from people fishing

The Federal 'Shark mitigation and deterrent measures' Senate Inquiry (2017) found substantial evidence that shark nets and catch-and-kill drumlines (used by the Queensland Shark Control Program and NSW Shark Meshing and Bather Protection Program to cull sharks) do not make any positive impact on safety, negatively impact the marine ecosystem, and provide beach goers with a false sense of security. They recommended these methods cease in favour of modern non-lethal technologies, however both states have thus far refused to comply with this recommendation.

Frequently asked questions

Evidence and Reports

Hoel & Chin (2020) — Scientific basis for global safety guidelines to reduce shark‑bite risk.

Tester (1963) — Attraction to odours from stressed fish.

Disclaimer:

This website provides factual and transparent information about the QLD Shark Control Program, including limitations and environmental impacts. It is not the official QLD Government SharkSmart website. It is designed to present information that is often omitted or misrepresented by DPI. For the government site, visit dpi.qld.gov.au/news-media/campaigns/sharksmart.